Volume 3 of The British Monthly is available in full on the Internet Archive

http://www.archive.org/details/britishmonthlyil03londuoft

[Page 77, column 1 in original pagination]

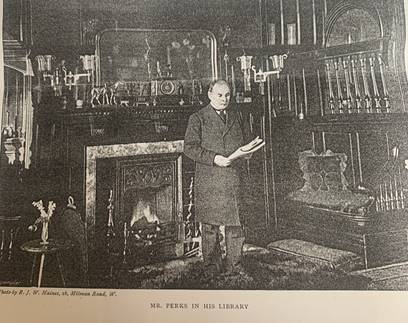

If we cannot get all we desire for England and the Church of Christ in these days, we have at least almost boundless facilities for making those desires known. The many-tongued organs of national, social, and religious aspiration — the platform, the pulpit, and the press — are accessible to every reformer and would-be reformer in the land. Of present desiderata that are making themselves loudly heard as the old year is in travail with the new, there is a little company of three which bear a strong family likeness to one another. England, we are told, needs not so much an increase in the number of her cultured and eloquent ministers as in the number of her fearlessly Christian laymen; secondly, the Free Churches need a stronger, more compact, more convinced, effective, and representative party in the House of Commons; thirdly, the Liberal party needs recruiting from that class which made it so powerful a humanitarian and progressive engine in the hands of Mr. Gladstone — the great and wealthy commercial middle-class. It is not necessarily an endorsement of these three great needs to say that no man in England realises each of them better, or indeed so well, as Mr. R. W. Perks. As a Christian layman his influence in the cause of righteousness, liberty, and personal godliness rivals that of any living minister. In the House of Commons there is no member better qualified than he to be the nucleus of a powerful Nonconformist party; while on the Opposition benches there is not a man who represents more widespread and powerful financial and commercial interests. Mr Perks may therefore be appropriately considered from this threefold point of view — not as the ideal Christian layman, Nonconformist M.P., and commercial representative — no man is that; but as the most successful and obtainable approximation. So regarded, the story of Mr. Perks’s life falls into three chapters — personal, commercial, and political. In reading it one feels how essentially modern a story it is, full of all that practical energy, passion for renovation and alteration, that restless, conquering struggle to adapt the ancient principles of faith and morals, no less than science and trade, to the changed conditions of the time, which have been the distinguishing marks more or less of every career which commenced its race since 1840.

[Page 77, column 2 in original pagination]

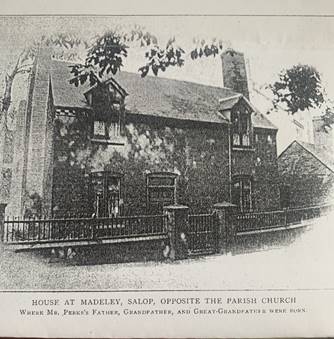

Robert William Perks is a “son of the manse”, and it is betraying no confidence to add that many another “parson’s son” has had a good reason to be thankful for that fact. His Methodist roots strike deep into the past. His father, the Rev. George T. Perks, was born four years after Waterloo in peaceful little Madeley, in Shropshire, sacred to every Methodist as being the parish of the saint of early Methodism John Fletcher. The grandfather of the present Mr. Perks was John Fletcher’s churchwarden, and on the death of Mrs. Fletcher he became the leader of her famous Society class[3] — one of the first to be formed in England. The Rev. G. T. Perks, M.A., who became President of the Conference in 1873, narrowly escaped becoming a clergyman, as Mr. Eyton, the Vicar of Madeley[4], intended him for the Church. One speculates whether, had his famous son been born in a parsonage instead of a manse, England would have been hearing during the last few years of a great Anglican “Million Scheme,” and have seen Mr. Perks advocating in the Church House at Westminster, under the chairmanship of the Archbishop of Canterbury or Lord Halifax, the famous principle of “one communicant one guinea.” Between 1850 and 1870 Mr. Perks’s father was one of a little group of Liberal Wesleyan ministers who fought a gallant battle to deliver Methodism from the domination of reactionary Toryism in Church and State. His colleagues were Dr. Punshon, Dr. Gervase Smith, Rev. Luke Wiseman, Charles Garrett, Dr. Ebenezer Jenkins, and William Arthur, all of whom have passed from the conflict with the exception of Dr. Jenkins, whose almost disembodied presence still hovers pathetically about the Conference platform. When stationed at Dalkeith in 1843, Mr. Perks, senior, married Miss Dodds[5], the daughter of a Scotch architect. Of his mother the “member for Methodism” says: “She was more or less of a Presbyterian to the end of her days. She dated everything from the disruption, and though a loyal Methodist preacher’s wife, never admitted that Methodism was needed in Scotland.” While at Dalkeith the Duke of Buccleuch became a great admirer of the young Methodist preacher, and frequently attended his chapel.

In the year 1846 a turn of the triennial wheel brought

[Page 78, column 1 in original pagination]

Mr. and Mrs. Perks to London[6], where the subject of this sketch was born, his father’s circuit being Hammersmith. Robert William Perks spent his early life, as the son of every Methodist minister does, in gipsy fashion, trekking now north and now south, for which dislocating itinerating there appears nothing to be said, except that it encourages the preaching of old sermons and saves the minister’s children from contracting dialects and brogues. Accordingly we hear of wanderings from Perth to London, from London to Manchester, from Manchester to Bath, then back again to London[7]. From the year 1858 to 1865, young Perks was a boy at New Kingswood School, the successor of the one founded near Bristol by John Wesley for the sons of his preachers, and where in the good old bad times the pupils rose at five in the morning, never had a holiday, and were forbidden to play. One of his school-fellows in those days was James Fletcher

[Page 78, column 2 in original pagination]

Moulton, now M.P. for Launceston, and one of Mr. Perks’s closest friends[8]. From Kingswood he was transferred for a short time to a private school in Clapham kept by a Mr. Jefferson[9], and then upon the urgent advice of his uncle, an Anglican clergyman[10], he entered King’s College, London. The family were then living in Wesley’s house in City Road, and Robert’s bedroom and study was the little chamber known as “Wesley’s praying-room.” City Road Chapel was then at the summit of its fame with enormous congregations, and the pathetic modern wail over deserted City sanctuaries was unknown. Mr. Perks possesses some curious memories of those far-away times. Boy-like, the two incidents which he recalls most vividly were the entry of Garibaldi into London[11], and the hanging of a number of pirates at Newgate, which he slipped off very early one morning to see[12]. Also he tells us that to his home one day came an old minister named Tranter, who lived to be over a hundred. The ancient preacher entranced by boy by telling him that

[Page 79, column 1 in original pagination]

when a boy himself he had tramped to London to attend John Wesley’s funeral, and that there was not a single house between the “Angel” at Islington and City Road Chapel, and that he well remembered getting over a stile at the top of Lombard Street into some fields[13].

At King’s College young Perks worked hard, intending to enter the Indian Civil Service, and carried off most of the college prizes. In these days, when a classical and literary curriculum is being elbowed out of fashion by exclusively technical subjects, it is well to remember that one of the foremost commercial financiers of the day was trained under that famous Preacher of the Rolls and enthusiastic historian of Elizabethan times and disciple of Francis Bacon — the Rev. Dr. Brewer, of King’s College[14]. Every week he made his pupil write an essay on some current

[Page 79, column 2 in original pagination]

event, so that when in 1872 that pupil entered a City lawyer’s office[15], where he received no pay, he was able to earn £200 a year by journalism. But that was thirty years ago — evidently. On the day his articles expired in 1876, he left this old-fashioned firm, and started business on his own account in partnership with Sir Henry Fowler[16]. For a quarter of a century that honourable and successful partnership lasted, its amity never once troubled by an unpleasant word or a difference. Two years ago, however, the extensive legal business was transferred to Mr. Perks’s only brother George, and both partners retired from active legal work[17].

Mr. Perks’s birthday and wedding-day coincide. On April 24th, 1878, he married Miss Edith Mewburn, of Wykham Park, Banbury, and went to reside at Chislehurst[18].

[Page 80, column 1 in original pagination]

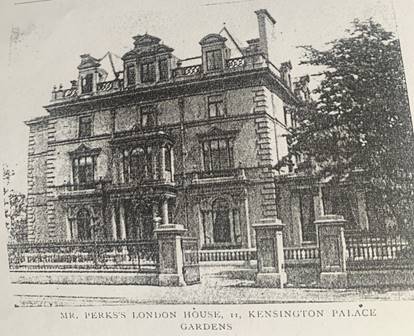

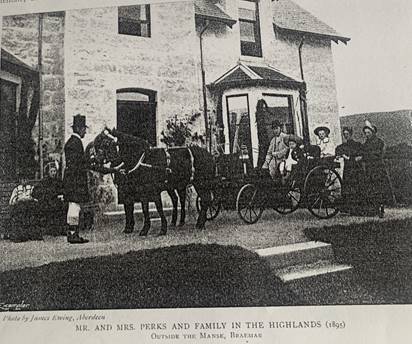

After sixteen years he removed to Kensington. The family of Mr. and Mrs. Perks numbers five — four girls, the eldest of whom is treasurer of the successful Young Leaguers’ Union, and one boy, Robert Malcolm Mewburn[19].

Mr. Perks’s devotion to the Church of his fathers has been intense and life-long, and innumerable are alike the offices he has filled and the services he has rendered. As early as eighteen he was a Sunday-school superintendent at Stoke Newington, where he commenced with two scholars, and in two years had gathered about him no less than four hundred. At the little village of Widmore, near to Chislehurst, he turned a school of forty into one of more than three hundred. Himself a young man, and as full of ambition for the Kingdom of

[Page 80, column 2 in original pagination]

Christ as for his own career, he threw himself at Highbury into work among youths of the most abandoned class, and speedily collected a class of over forty members. The year 1878 was a memorable one in Methodism. Up to that time the Conference had consisted entirely of ministers, but that year lay members were admitted, and Mr. Perks went as representative of the First London District, being at the top of the poll[20]. He has been elected every year since. Among the bewildering number of church treasurer- and secretaryships which he has held, it may be mentioned here that he was secretary of the first Oecumenical Congress held in London in 1881, and treasurer of the recent Congress in 1901, when he and Mrs. Perks entertained all the members, numbering sixteen hundred people, including the coloured delegates, at their beautiful mansion in Kensington.

Turning now to the great Methodist movements with which Mr. Perks has been most intimately associated during the past twenty-five years, they will be found to be five. The first was the agitation for Methodist union. For a moment this ideal is under a cloud, notwithstanding that federal ideas are in the air. He was long ago convinced that sooner or later British Methodism must follow the example of Canada and Australia, and unite in one firm, organic whole all the spiritual children of John Wesley, whether they call themselves Free or Primitive of Bible Christian. And in this conviction and effort Mr. Perks found an eloquent colleague in his friend the late Hugh Price Hughes. “In this way,” he says, “British Methodism must prepare herself for the time when, the Church of England being disestablished, she will be numerically the most powerful Protestant Church in England.” From its inception, in which he took a leading part, Mr. Perks has given to the Free Church Federation movement his utmost sympathy and the aid both of his advocacy and his purse. At the present moment he is its treasurer, as he also is of the metropolitan Council. The third movement, in which he played the part of antagonist and critic, and which went by the nickname of the “No Methodist Bishop” movement, was a proposal to institute a new ecclesiastical order under the euphonious name of “separated chairman.” The idea — which is happily now dead — was to free the chairmen of districts from circuit and pastoral charge, so that they might exer-

[Page 81, column 1 in original pagination]

cise a disciplinary and advisory oversight of their “diocese.” Mr. Perks sprang into the arena, and severely attacked the proposal in a famous pamphlet called “No Methodist Bishops.”[21] It was in vain that Dr. Pope and Mr. Price Hughes repudiated the name of bishop — the latter convulsing the Birmingham Conference by calling the pamphlet “that political squib with which my friend Mr. Perks amused himself during his Christmas holiday.” But the Conference would not have it. This was one of the very few occasions on which Mr. Perks voted in a different lobby from his friend Mr. Hughes.

What Mr. Perks has done on behalf of the great London and provincial missions everybody knows. From the commencement of the former in St. James’s Hall he has been its treasurer and most generous subscriber, and an annual meeting without him in the chair is unthinkable. Recently, however, he has been unable to approve of some of the methods adopted at the great West End Mission, and has consequently taken no prominent part in the work of that branch. And when to this severe loss must be added the removal of its beloved superintendent[22], one trembles for the future of what has hitherto been so magnificent an undertaking.

Lastly, no one needs to be told that the world-known

[Page 81, column 2 in original pagination]

“Twentieth Century Scheme” was the product of Mr. Perks’s fertile brain. How impracticable it seemed at first! What unparalleled resources, generosity, and sacrifice it has revealed! Hardly had the originator brought forward tentatively his vast scheme, than the great democratic cry of “One man one guinea” was echoed and re-echoed throughout the land — a fervent battle-cry which has resulted in £950,000 being paid or promised. At once Mr. Perks gave up twelve months to literally scouring the land, and to his splendid advocacy, joined with that of Mr. Hughes, the ultimate completion of the “Million Scheme” is largely due. And if imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, Mr. Perks must be pronounced the most flattered Nonconformist layman in England, for most of the other Nonconformist Churches have commandeered his audacious idea in one form or another. The latest and most daring of his moves in connection with this movement was the purchase of the Aquarium. It is not too much to say that the announcement was received with delighted consternation by the whole country. From the outset Mr. Perks had had his eye on two sites — one opposite the National Gallery, the other the Aquarium. He soon found that the former was too costly, and so turned to the Aquarium. For a long time he doubted if it could be secured, but at length the way opened. At present it is not possible to say how much land will be used and how much let on lease. Probably, Mr. Perks says, at least 40,000 feet will be required for Church purposes. As to the new building to be erected, Mr. Perks is very strong in insisting that it must be monumental, and a structure worthy of the Methodist Church. Negotiations are still pending with Mrs. Langtry[23], and nothing is finally settled.

Such in briefest outline has been the life of Mr. R. W. Perks in its domestic and Methodist aspects. And no one will deny that it is typical of what is so urgently needed in these modern days — devotion to the moral and spiritual needs of England on the part of her wealthy and cultured sons. Retracing our steps to gain some idea of Mr. Perks’s commercial career, a landscape of picturesque undertakings

[Page 82, column 1 in original pagination]

unrivalled in their enterprise and success greets us. He has for many years been engaged in some of the most important commercial enterprises in Europe, and has enjoyed the friendship and confidence of many distinguished men. As a lawyer he trained himself for mercantile and Admiralty law, and established himself in Leadenhall Street with that object in view. But almost immediately he was embarked in Parliamentary practice and business incidental to railways and great public works. He has himself told the story of the curious way in which he got his first Parliamentary work[24]: “I was spending my summer holiday in Llandudno in 1877 and was struck with the heavy tolls charged on Conway Bridge, and investigated the history of Telford’s celebrated structure in some detail. One day, as I was sitting in the coffee-room of the Imperial Hotel, I saw a coach and four drive up, and four men enter the room loudly complaining of the tolls they had just had to pay.

“Though quite a youngster I chimed in and said, ‘Well, gentlemen you deserve to pay those rates, for years ago you should have taken the bridge from the Crown, vested it in Local Commissioners, and have reduced the rates.’ ‘How are we to do it?’ Asked Sir Richard Bulkeley[25]. ‘I will show you,’ I said. The result was that I was engaged to bring a bill into Parliament which I successfully carried, cancelling the debt due to the Treasury and vesting the bridge in local authorities. That was my first bill in Parliament. Mr. Pennant, now Lord Penrhyn, was good enough to mention my name to some of his friends, and the Conway Bridge Bill led to several others.”

Mr. Perks’s staunchest and most accomplished business friend was the great railway magnate, Sir Edward Watkin,

[Page 82, column 2 in original pagination]

for which valuable connection he was indebted to his late father-in-law, Mr. Mewburn[26]. The first important work he had to do for Sir Edward was to go over to France to report confidentially upon the extensions of the Northern of France Railway, the capabilities of Trêport Harbour, and the possibility of securing the control of the Abbeville and Trêport railways. In carrying this out Mr. Perks made the acquaintance of the late Comte de Paris, with whom he stayed at the Château d’En[27]. The intention, which was frustrated by dissensions on the South-Eastern Railway board, was to have used Trêport, which is forty miles nearer Paris than Boulogne, as a competing port to Dieppe. Shortly afterwards Sir Edward Watkin appointed Mr. Perks solicitor of the Metropolitan Railway — a post worth from £3,000 to £4,000 a year, and which he held till he entered Parliament in 1892[28].

One of Mr. Perks’s commercial dreams is a Channel Tunnel. Through the influence of Sir Edward Watkin he was engaged some time ago, it will be remembered, in an endeavour to translate the dream into actuality. He fought the scheme in all the courts of law in opposition to the Crown, and took charge of the whole proceedings before the Select Committee presided over by Lord Lansdowne, where the scheme was rejected by five to four[29]. But he is still a strong believer in the tunnel. It would improve the relations between Englishmen and their continental neighbours, besides being one of the finest commercial investments in the world, far exceeding in value even the Suez Canal. In time of war it could be immediately flooded, and what an advantage to a traveller to be able to get into his train at Charing Cross at four o’clock and without getting out find himself in Paris by ten. Mr. Perks

[Page 83, column 1 in original pagination]

must be content to wait for a more enlightened and pacific era.

In connection with these enterprises Mr. Perks made the acquaintance of two very distinguished Frenchmen — M. Ferdinand de Lesseps and M. Leon Say. The two British statesmen with whom this project brought him into constant contact were John Bright, a firm friend to the tunnel, and Lord Randolph Churchill, an opponent, though not a strong one. Among his papers Mr. Perks still retain a lengthy MSS. prepared for Mr. Gladstone, and covered with the notes used by him in his famous defence of the scheme in the House of Commons[30]. Personal jealousies, rivalries, and interests, Mr. Perks thinks, had far more to do with wrecking the tunnel than any question of national danger. And still the long story of great undertakings is not ended.

Sir Edward Watkin introduced Mr. Perks to another famous engineering potentate, the late Thomas Andrew Walker, contractor of the Severn Tunnel. Besides being an accomplished engineer, Mr. Walker was a cultured scholar and devout Christian. The great Barry Docks and railways in South Wales, the Preston Docks, the Manchester Ship Canal, and the vast harbour and dock works in Buenos Ayres were some of the great public works in which Mr. Perks was associated with Mr. Walker. It was only natural, therefore, that when the latter was prematurely stricken down in 1888 the burden of completing these multifarious enterprises should fall

[Page 83, column 2 in original pagination]

on Mr. Perks[31]. Now they are all finished, and he is a partner with his late chief’s nephew. Having completed for the Argentine Government, at a cost of ten millions sterling, the harbour, the new company[32] is now engaged in constructing docks and quays for the Brazilian Government at Rio. They are also the contractors for the proposed Georgian Bay Canal from the Great Lakes to the St. Lawrence, sanctioned by the Canadian Government. In recognition of his many services Mr. Perks was years ago elected associate corporate member of the Institute of Civil Engineers[33]. In 1901 there fell to Mr. Perks, the chairmanship of the Metropolitan District Railway, in which he has a large interest, and to his credit it may be said that he is responsible for the arrangements for converting the whole of that line into an electric railway.

One of the latest achievements of this indefatigable man has been to pilot through Parliament four important Tube electric railways, and he recently negotiated on behalf of Messrs. Speyer Brothers, the purchase of the controlling interest in the London United Tramways, which was followed by the withdrawal of Mr. Pierpoint Morgan’s tube railways[34]. Mr. Perks sees no valid reason why the District Railway should not unite with the Metropolitan for all practical purposes. And lastly — and one’s breath gives out in following these giant concerns — Mr. Perks was engaged with Mr. Walker on the survey of the great Russian railway, 1,400 miles long, from St. Petersburg to Viatka and Vologda, and upon this business he met M. Witte, the most powerful of the Czar’s ministers. He has risen quite from the ranks by sheer force of character; his policy is anti-war and commercially progressive; and Mr. Perks has a high opinion of him and of his knowledge of British commercial measures[35]. To complete the tale of Mr. Perks’s famous commercial associates, the name of Sir Wilfrid

[Page 84, column 1 in original pagination]

Laurier, the Canadian Premier, and Dr. Robert Pelligrini, late President of the Argentine Republic, should be mentioned, together with Nabur Pasha, who was his close friend, Mr. Perks having considerable interests in Egypt[36].

Enough has surely now been advanced to show that in Mr. R. W. Perks the Liberal party have a typical representative of the great commercial and financial classes. It is now more than time for some brief sketch of Mr. Perks’s relation to political life. Not till the year 1886 did he take any practical interest in Imperial or municipal affairs. Though frequently asked to stand for Parliament, his business was too monopolising, and municipal matters seem to have attracted him but little. After the disastrous election of that year, urged by Mr. Schnadhorst and encouraged by Mr. Gladstone himself, he set to work to reorganise the Liberal party in North Lincolnshire, and in 1892 was returned by a majority of 800 for Louth,[37] for which constituency he still sits. He was then a Liberal and Home Ruler, and consistently supported Mr. Gladstone in his Irish legislation.

It is often asked why Mr. Perks has remained plain “Mr.,” when so many Methodist laymen have received “honours.” The answer is that the Liberal Whips offered him a knighthood in 1894, and he declined it. In the succeeding election he fought and won Louth with increased majorities[38]. Last election Mr. Perks pronounced against the Irish alliance, and stood as an avowed supporter of the South African war. While he strongly blamed the Government for their disastrous policy which led to the war, and for their condition of unpreparedness, also for much of their conduct of the campaign, he held that the existence of the two Republics as independent states was impossible, and that President Kruger’s ultimatum, coupled with the Boer invasion of our territories, compelled Great Britain to defend those territories, and absorb them in what he hopes will one day become a British South African dominion of self-governing federated states. It is well known, further that Mr. Perks was one of the original founders of the Imperial Liberal Council, which subsequently became the Liberal League[39].

Mr. Perks’s own voice is not frequently heard in the House, by no means so frequently as is desired by the tens of thousands of Nonconformists who look to him to represent their position as few others are able to do. When taxed with this silence, Mr. Perks thus defends, or at least explains, himself: First, there are his heavy business,

[Page 84, column 2 in original pagination]

Methodist, and philanthropic engagements to be kept. “A man who has to be at his work in the City shortly after nine every morning,” he says, “cannot go to the House at two and sit there till midnight. Moreover, the methods of procedure and the habits of the House of Commons cannot be congenial to business men accustomed to act promptly, to economise time, and to push aside trivialities and delegate details.” He thinks — and those concerned should take the compliment to heart — that men shine in Parliament who would make no progress in commercial and city life, and who would never be trusted with serious financial and mercantile responsibilities. “The House of Commons is a place for talkers rather than for workers” is his disheartening conviction. But he thinks even more discouragingly than this, that office can have few attractions for men who do not need a salary, and who have seen sufficiently behind the scenes of “office.” All this, if true, bodes ill for the future of England, as also does Mr. Perks’s conviction — which others beside himself have been driven to — that the House as a body is not the powerful assembly it was thirty-five years ago. Power has, unfortunately, passed into the hands of the great administrative departments and out of the hands of the rank and file. “The Empire,” he says, “is governed, not by the popular assembly, but by a bureaucracy consisting of permanent officials.” On the Education Bill — if Education Bill it must be called — Mr. Perks’s views are well known. From the outset he regarded it as a clerical one, initiated by the Anglican and Roman clergy, and directly aimed at Nonconformity. He has spoken several times in the House against it, and attended scores of meetings all over the country, and perhaps in this latter way has done best service to our cause[40]; and no Liberal member has done more to show by incontrovertible facts and cases the measure of the wrong which the bill will inflict on poor Nonconformists in outlying country parishes. It remains but to say that he is president of the Eastern Counties Liberal Federation, and was chairman of the Nonconformists Political Council, whose meetings were suspended during the war.

Such is the career — rich in daring and successful enterprises, crowded with innumerable benevolences and disinterested advocacies, wholly inspired with an earnest and honourable Christian spirit — of one whom Methodism, and the entire Free Churches of England, delights to honour.

[Page 85 in original pagination]

[This photograph occupied the whole of that page]

Endnotes

[1] The British Monthly was subtitled: An Illustrated Record of Religious Life and Work. Its first issue was that of December 1900, which was published on 21 November 1900. It was founded by William Robertson Nicoll (1851-1923), who had founded The British Weekly in 1886. Nicoll had been a minister of the Scottish Free Church until retiring following a severe attack of typhoid in 1885. He was a member of the Council of the Liberal League (R.W. Perks, Notes for an Autobiography, p. 141).

[2] The December 1902 issue of The British Monthly (p. 7) stated: “The next number of The British Monthly will be published on December 20, and should be on sale at all Newsagents’ and Booksellers’ on that date.” And it foreshadowed that the January issue would include a “fully illustrated sketch (containing much fresh matter) of Mr. R. W. Perks, M.P.”

[3] It was the great-grandfather of R.W. Perks who had been John Fletcher’s churchwarden. George Perks (1752-1833) was the subject of a memoir written by Mary Tooth, published in The Wesleyan Methodist Magazine, Volume 14, 1835, pp. 895-900. It was his son William Perks (1781-1831) who was the father of the Rev. George Thomas Perks (1819-1877) and grandfather of R. W. Perks. It is perhaps worth noting that there is also an error in the caption to the photograph of the Perks family’s house in Madeley published on page 78 here. It is true that both the father and the grandfather of R. W. Perks were born in that house. But Perks’s great-grandfather was born in Higford. He did not commence living in Madeley until March 1781, two years after his marriage (see Mary Tooth, “Memoir of Mr. George Perks of Madeley”, p. 895).

[4] John Eyton (1779-1823) was never the Vicar of Madeley. He was the Vicar of Wellington in Shropshire from 1802 to 1823. George Thomas Perks’s mother was from Wellington, and Eyton had been the celebrant at her marriage to George’s father in 1817. Eyton was a friend of Mary Fletcher and her companion Mary Tooth, and was probably a frequent visitor to Madeley during the years Perks’s father was a young child there.

[5] George Thomas Perks (1819-1877) married Mary Dodds in August 1845.

[6] It was at the Wesleyan Methodist Conference of 1847 that G. T. Perks was appointed to the Hammersmith circuit. He had been appointed to the Dalkeith circuit in 1843, and remained there for two years before being appointed to the Perth circuit by the W. M. Conference of 1845. When G. T. Perks and his wife moved from Perth to London in August 1847, it was not because the “triennial wheel” had moved full circle at that time.

[7] Having moved from Perth to Hammersmith in August 1847, G. T. Perks moved to the first Manchester circuit in 1850, to the second Manchester circuit in 1853, to Bath in 1856, to Bristol North in 1859, and to the City Road circuit in London in 1862.

[8] It was John Fletcher Moulton (1844-1921) who was M.P. for Launceston at the time this article was published (having been elected in 1898). His time at Kingswood overlapped with Perks’s time there, but it was one of his brothers, Richard Green Moulton (1849-1924), who had been in the same class as Perks during his years at the school.

[9] Henry Jefferson (1826-1893) was headmaster of the New Kingswood school from 1855 to 1865. Upon leaving Kingswood, he established a private school at 27 Oberstein Road, New Wandsworth. Perks attended that school for the 1865-66 academic year and successfully sat for the senior level of the Oxford Local Examinations while there. It was not until January 1867 that Jefferson relocated his school to Clapham Common.

[10] The reference here is to Charles Thomas Perks (c. 1825-1894), one of G. T. Perks’s younger brothers. R. W. Perks’s “Uncle Charles” sailed for Australia in January 1851, having undertaken theological studies at King’s College London during 1849 and 1850. In 1851 he was appointed to be the founding vicar at St. Stephen’s, Richmond, in Melbourne. See Morna Sturrock, Fruitful Mother: St. Stephen’s Richmond Parish History, 1851-1991, St. Stephen’s Parish Publishing Committee, Melbourne, 1993. He spent a sabbatical year in the U.K. in 1858 to 1859, and made another extended visit to Britain in 1869 to 1870. He died in Melbourne in February 1894.

[11] Garibaldi’s procession along City Road was on Wednesday 20 April 1864 (see The Times, 21 April 1864, p. 14).

[12] Five pirates were hanged on 22 February 1864 in the public street in front of Newgate prison. This “spectacle” attracted a large crowd and was the subject of a number of newspaper editorials condemning the continued practice of public executions in Britain (see for example The Newcastle Daily Journal, 24 February 1864, p. 2). The date of the last public execution in Britain was 26 May 1868. Note that both this incident and Garibaldi’s entry into London took place more than a year before Perks left New Kingswood School.

[13] The Rev. William Tranter was born in Little Dawley, near Madeley, in May 1778 and died in Salisbury in February 1879. In his youth he had attended Wesleyan classes in Madeley and thus is likely to have known the Perks family from that time.

[14] Dr. John Sherren Brewer (1810-1879) was professor of English language and literature, and lecturer in modern history, at King’s College during the years Perks was a student there.

[15] The City legal practice at which R. W. Perks served his articles was Messrs. De Jersey and Micklem of Gresham Street. The year he commenced his articles with that firm appears to have been 1870.

[16] R. W. Perks completed the requirements for his qualification as a solicitor in April 1875 and was duly sworn-in as a solicitor in the High Court of Chancery on 20 April 1875. His commencement “in business on his own account in partnership with Sir Henry Fowler” occurred in 1875, not in 1876 as stated here.

[17] The London Gazette of 5 February 1901 (p. 788) published a notice dated 28 January 1901, stating: “the Partnership which has been carried on by Sir Henry Hartley Fowler M.P., Robert William Perks, M.P., and George Dodds Perks, under the firm of Fowler, Perks and Co., in the business of Solicitors, at 9, Clement’s lane, in the city of London, has been dissolved by mutual consent as from the 31st day of December, 1900. The business will continue to be carried on by the said Geroge Dodds Perks alone, under the same title, and at the same place, and he will receive and pay all debts due to and owing by the said firm.” George Dodds Perks was the youngest of the eight children of George Thomas Perks and Mary Dodds. Born in March 1864, he was 13 when his father died. He attended New Kingswood School from 1878 to 1881, following which he became an articled clerk in the Fowler and Perks legal practice.

[18] Edith was born in Halifax, Yorkshire, in July 1854, the youngest of the four daughters of William Mewburn (1817-1900) and Maria née Tew (1822-1902). William Mewburn was a member of the Manchester stock exchange and a high profile Wesleyan Methodist layman. He bought “the mansion and manor” at Wykham Park, just outside Banbury, in 1867 (The Methodist Recorder, 1 November 1867, p. 381), having taken a lease on the property in 1865. In November 1875, John Hartley Perks recorded in his diary R. W. Perks had written to him telling him that he had become “engaged to Miss Mewburn of Banbury.”

[19] Edith’s four daughters and son were all born in Chislehurst prior to the family’s move to 11 Kensington Palace Gardens in 1894. Gertrude was born in September 1879, Mildred Mewburn in March 1882, Edith Mary in February 1884, Margaret Hilda in December 1885, and Robert Malcolm Mewburn in July 1892. In regard to Gertrude and the Young Leaguers’ Union, see endnote 9 to Chapter Ten of Denis Crane’s 1909 biography of R. W. Perks on this website.

[20] See Owen E. Covick, “The Lay Representatives at the 1878 Wesleyan Conference and R. W. Perks”, Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society, Volume 63, Part 5, Summer 2022, pp. 208-222.

[21] Perks’s 31 page pamphlet “No Methodist Bishops” was subtitled: “An appeal to the Ministers and Laymen of the Wesleyan Methodist Church to reject the proposals of the Conference Committee to impose an Episcopate upon the Connexion.” It was published during the latter part of January 1894.

[22] The reference here is to the “removal” through death of Hugh Price Hughes, who died on 17 November 1902. He had been appointed the first superintendent of the West London Mission in 1885.

[23] The provisional agreement for the purchase of the Royal Aquarium site was made on 18 July 1902, and Perks stated this publicly on 23 July 1902 (The Methodist Times, 24 July 1902, pp. 505-506). The vendor was a limited liability company established in 1874: “The Royal Aquarium and Summer and Winter Gardens Society Ltd.” That company had leased-out some portions of the site — notably that occupied by the Imperial Theatre. Lily Langtry was the holder of that particular lease, which had some fourteen years still to run. She was said to have spent more than £30,000 on the property (The Weekly Irish Times, 2 August 1902, p. 12). As this article states, negotiations as to the terms on which Mrs. Langtry might be willing to sell back her lease to the new proprietors of the site, were at an early stage in December 1902/January 1903.

[24] The Fowler and Perks legal practice established at 147 Leadenhall Street in 1875 undertook at least two pieces of “Parliamentary work” prior to the one referred to here. There was the application for a Provisional Order on behalf of the Llandudno Pier Company Limited (see London Gazette, 23 November 1875, pp. 5773-5774). And there was the Methodist Conference Bill for the 1876 session of Parliament (see ibid, 26 November 1875, pp. 5836-5837).

[25] Sir Richard Mostyn Lewis Williams-Bulkeley (1833-1884) had been appointed Constable of Conway Castle in 1874. In January 1877, as Mayor of Conway, he presided over a large public meeting held at the Guildhall, Conway, “with the object of taking steps to obtain a reduction in the tolls demanded at the Conway suspensions bridge” (Liverpool Mercury, 13 January 1877, p. 7). In Sir Richard’s introductory comments at the meeting, he referred to “The very able and exhaustive report prepared by Mr. Perks … which has been widely circulated” (loc. cit.). This seems to put a question mark over whether the chance encounter in the coffee-room of the Imperial Hotel took place in the summer of 1877 — as stated here. For more on Perks’s activities in North Wales during this period, see Owen E. Covick, “R. W. Perks: From ‘Son of the Manse’ to ‘Man of the City’”, Paper presented to the 2009 Conference of the Association of Business Historians, University of Liverpool Management School, July 2009.

[26] It is interesting that this article is quite explicit in stating that Perks owed his (very fruitful) business connection with Sir Edward Watkin to William Mewburn. For evidence of the close business relationship between Watkin and William Mewburn during the years immediately preceding Perks commencing to undertake work for Watkin, see Owen E. Covick, “Watkin’s Struggle at the S.E.R. Board 1876-79, and R. W. Perks”, published as an e-supplement to the Journal of the Railway and Canal Historical Society, 2019.

[27] Perks’s first visit to Trêport on behalf of Watkin, appears to have been in September 1879. Earlier in the 1870s, Watkin had taken a serious interest in the idea of building a port at Dungeness and establishing a new cross-channel steamer service between there and Trêport, about 15 miles to the east of Dieppe. But his colleagues on the board of the South-Eastern Railway were not enthusiastic and the idea was shelved (see David Hodgkins, The Second Railway King: The Life and Times of Sir Edward Watkin 1819-1901, pp. 441-443). Following the defeat of the anti-Watkin grouping in the February 1879 S.E.R. board elections, and Watkin’s consolidation of his victory in the months that followed, this idea was revived (see ibid, pp. 505-507). The Comte de Paris was a significant shareholder in the small railway connecting Trêport with the main line to Paris. The name of his Chateau is misprinted here. It should read “the Chateau d’Eu.”

[28] Perks formally took over duties as the solicitor of the Metropolitan Railway Company on 17 February 1882, the board having given his predecessor six months notice of termination on 17 August 1881, and having agreed on 30 August 1881 to the terms under which Perks was to take over the role. These included remuneration at the rate of £2,500 per year, with this “base” remuneration later increased to £3,500 p.a., and supplemented from time to time with various bonuses. See endnote 9 to Chapter Three of Denis Crane’s 1909 biography of Perks on this rwperksproject website.

[29] The Select Committee referred to here first met on 20 April 1883, heard evidence through to mid-June, and convened to determine its Report on 10 July 1883. The Committee was comprised of ten members, five from the House of Lords and five from the House of Commons. All ten were present at the final meeting on 10 July 1883. Lord Lansdowne’s draft report, which was in favour of the Channel Tunnel scheme, was rejected by six votes to four, not “by five to four” as stated here.

[30] The House of Commons speech by Gladstone referred to here was given on 27 June 1888 in the debate on the Second Reading of the Channel Tunnel (Experimental Works) Bill.

[31] Thomas Andrew Walker died on 25 November 1889. Perks was the legal and financial adviser to the three executors of the T. A. Walker Estate (Charles Hay Walker, Louis Philip Nott, and Thomas James Reeves). In that capacity, Perks organised for a series of private Acts of Parliament to be obtained to allow the executors to continue the very substantial business enterprise which Walker had succeeded in building up.

[32] The “new company” referred to here was the limited liability company “C. H. Walker and Co Ltd”, registered by Perks on 20 April 1898. T. A. Walker’s nephew Charles Hay Walker (1860-1942) and R. W. Perks were this company’s principal shareholders and its two directors. The terms of the third of the Walker Estate Acts provided for the remaining business activities of the Estate to be transferred to this company. See the entry for Charles Hay Walker published in volume three of the Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers, London, 2014, pp. 627-629.

[33] Perks was elected an Associate of the Institution of Civil Engineers on 5 March 1878.

[34] The purchase by Messrs. Speyer Brothers of a controlling interest in London United Tramways was agreed upon during September 1902, but not publicly disclosed until 21 October 1902. This takeover of L.U.T. meant that a projected deep-level underground line from Hammersmith to the City, being promoted by J. P. Morgan in conjunction with L.U.T., was effectively blocked from receiving Parliamentary authorisation in the 1902 session. The maintenance of secrecy regarding the L.U.T. takeover until 21 October 1902 meant that the Morgan camp had very little time available for drawing-up modified Bills for the 1903 session and publishing appropriate notices of these by the required deadlines. Perks and the Speyers firm came in for criticism in the press and in Parliament for the manner in which the Morgan scheme had been blocked. See section B7 of Owen E. Covick, “R.W. Perks, C.T. Yerkes and private sector financing of urban transport infrastructure in London 1900-1907” paper presented to the 2001 Conference of the Association of Business Historians, Portsmouth (U.K.), June 2001.

[35] Perks’s visit to Russia was in August to September of 1899. Sergei Witte (1849-1915) was at that stage the Finance Minister of Russia.

[36] Perks’s main business interest in Egypt appears to have been through the Khedivial Mail Steamship and Graving Dock Company Ltd which he registered on 30 April 1898. The prospectus of this company was published in June 1898, and the construction of its graving dock was undertaken by C. H. Walker and Co. Ltd (see note 32 above). The “Nabur Pasha” referred to here may have been Nubar Pasha (1825-1899) who served as prime minister of Egypt on three separate occasions. Following his retirement from office in November 1895, he divided his time between Cairo and Paris where he died in January 1899. It is possible though, that the reference may be to Boghos Nubar Pasha (1856-1946), the son of Nubar Pasha (1825-1899).

[37] Perks’s majority in the July 1892 election weas 839.

[38] Perks’s majority in the July 1895 election was 412, — clearly a decrease compared with July 1892.

[39] The Imperial Liberal Council was established in April 1900. The Liberal League was formally founded in February 1902. See endnotes 9 and 10 to Chapter Nine of Denis Crane’s 1909 biography of Perks on this rwperksproject website.

[40] The use of the phrase “our cause” here seems to suggest that the writer of this article was happy to indicate strongly held personal views regarding the Balfour Education Bill, which at the time this article was published had passed the House of Commons and had been forwarded to the House of Lords.